Today is Mahalaya, the 19th of September 2017. As I sit in Kolkata and the evening turns to night around me, Puja fever is in full swing. There are a few more days to go before my own holidays begin, but they’ve already begun in Tehatta. For the people on the other hand, it would not be so much Durga Puja as the Laxmi Puja that follows. Nobody could explain why the latter is more important there, but it is. My colleagues, of course, would not be in Tehatta, but in various districts of the state, or even outside. There they would be celebrating in their own way, even as I enjoy these holidays in my own style. Tehatta would celebrate in one way, my colleagues in their own ways, me in my own. But when this season dies out, they will return to Tehatta, and I will still be here, in Kolkata.

The choice of course, was always my own. It is stupid of a young man to say that the decisions he makes in life have been foisted upon him by circumstances. No matter how much I whined about folks at home wishing me to work close to my residence; no matter how much I talked about needing to stay in Kolkata to do my PhD; no matter anything else- the fact remains that I wanted to return to Kolkata, and did so. In fact, from the very first day I went to Tehatta, I knew that one day I would want to return and return after having achieved something.

I don’t know if I did manage to achieve anything. Yes, my bank balance appears a lot fuller. Also, my heart is full of memories, only a few of which I have pasted in my blog. But those were not what I had been sent there for. Did I really manage to help the students who studied there? Did I, with my faltering Bengali and poor knowledge of these students’ needs, really manage to do better than what someone who has risen from their background would have done ? Was the PSC right in reposing faith in a person like me -full of high concepts but with little grasp of reality ? I don’t know.

But Tehatta tolerated me, and grew on me. And when I chose to leave, I did so knowing full well the decision I was making was my own. I had my reasons, and explicating them here will not cork the bottle of nostalgia that is overflowing right now. Tehatta could have left me behind quickly, and if it did so, I would not have developed the memories I have. It could have stayed with me for so long that I would have made it a semi-permanent part of my life. But it did neither, or rather, I didn’t allow it to. Hence, I had joy and learnt a lot but also had a constant understanding that I was often counting the days till I would get a chance to move closer home. Such is life – it forces you to develop bonds before asking you to break them and move on.

With all these conflicting emotions, I must pen the last part of this series. One of the easier ways to do this would probably be just to enumerate the facts. I’ll start with those. You see, back when I had applied for PSC, I had also applied for CSC, the service that recruits teachers for sponsored colleges. But the interviews for the latter dragged on indefinitely – an entire year in fact – and when they concluded, it was another couple of months before I got my counselling. Still more months passed before the interview took place, and another before I could formally join the new institution. In between, I ended up spending half a year in Bhawanipur and a year and a half in Tehatta.

But it was never clear that I would be able to leave. Colleges in Kolkata – which I was aiming for – were pitiably few compared to the demand, and chances appeared slim. I didn’t know that I would secure a decent rank and due to a number of factors including my competitors’ preferences, would manage to secure an interview at one of the most reputed colleges of the city. Neither did I know that I would be selected, or that I would have to wear my sole (and soul) out getting the release from my Tehatta service. I didn’t know any of it, and so the service in Tehatta was focused on Tehatta only, coupled with the occasional googling of CSC to see if any updates had been posted.

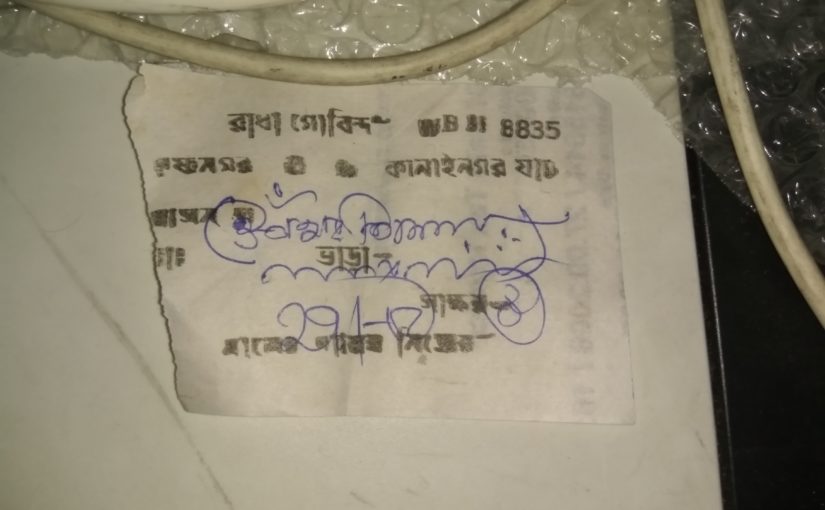

As my service in Tehatta collapsed in a series of visits to Bikash Bhavan to obtain the release orders, I became acutely aware that very soon I would no longer be heading to Tehatta. No longer would I be planning my tickets well in advance, or chewing my nails wondering if I would get a seat in the unreserved compartments if the booking status turned up as “Waiting”. No longer would I make 5 hour journeys that sucked the juice out of my bones, but allowed me to experience Tehatta in all its glory. No longer would I be a member of the West Bengal Education Service, and be counted as a gazetted officer. I would lead a different life, albeit under the same education system of West Bengal.

It was then that I conceptualized the idea of penning my ideas. Even before I had obtained my final release orders, I was wondering what all I would pen down. Starting my writing in June, I kept working through the monsoon months. Today, in late September, with three months already done at my new institution, I am at the final stage of the series.

In this time, a lot has happened. My colleagues knew that I had been selected, and coaxed me into telling them that I had opted for a college that had an interview stage. When I got through the interview, they knew it was only a time before the Kolkata boy returned to Kolkata. And so it happened. I put in my papers and began the long process of obtaining the release. Thankfully, it was May by the time I put in my papers, and the academic year was almost over. I had finished my course for the two years (the third year didn’t exist yet) well in advance, and the students didn’t suffer. In fact, they were hardly coming to college at all after April. Since the time was so short, I didn’t tell them face to face that I was leaving. I don’t know what their reaction would have been, but somehow it required a little more courage than what I could muster. Maybe because this leaving was no transfer – I was leaving because I wanted to. How do I explain that ?

Anyhow, Tehatta didn’t demand much of me in my final days there. There were Part III exams going on, and this meant we had to go for invigilation on specific days. That was fine, for it gave me time to run around Bikash Bhavan. But it also meant I was hardly ever staying there, since the invigilation days were hardly back to back ones. My Tehatta experience had been curtailed already, and this added to the nostalgia. As my colleagues ran around and planned for the next academic year, I felt I was in limbo – waiting to leave one place but not knowing anything about the new one. I knew I had to leave, but I wanted to leave on a better note. Better in what sense? I couldn’t tell, but I guess a perfect goodbye doesn’t exist.

I gave up my camp on the last day of May. Economic logic told me that I hadn’t been staying there for over a month, and there was every possibility that I would get my release within June. It simply made no sense to hold onto the rooms for another month. I had already told the landlady of my intentions (disguised as transfer – why did I do that?). This fulfilled the one month notice requirement. True, I could have gone back on my statement at any moment, but then again, why should I ? Life was takin me away from Tehatta, and I simply had to go with the flow.

One day before the final one, I had been given invigilation duty. That, unbeknownst to me, was the last full day of work I did at Tehatta. It was awfully dull, staring at students and occasionally confiscating study material from them. This gave me occasion to roam around the campus, and marvel at all that had changed since I had arrived. We now had beautifully whitewashed walls, a gate with tiled designs, an entire second floor that was almost complete (sadly, as of writing, it is still not in use from what I hear), grounds that had been decorated (though exactly for what still remained unclear) and a functioning canteen. It was still dusty, and the halls were still quite empty. I had believed that one day these would be filled up. Maybe they will be, but I wouldn’t be there to see it.

As I roamed around, I also noted the classes and the small things that had made up my life as a teacher in Tehatta Government College. For one, the first room assigned for history classes was Room No. 3. It was the same number as the classroom where I had studied as an undergraduate student in Presidency. That Room No. 3 had become an icon of our existence. I couldn’t say whether this room would have the same impact on my students, but it had a special relevance for me nonetheless. This, despite it later being turned into the Chemistry lab, and the history class being shifted upstairs, and then again because a smart classroom had to be created.

Another small but lovely part of my life was my locker number. Back when I had joined, there were far more lockers than teachers, and I had a good amount of choice. I chose one on the top left, and didn’t notice the number at the time. Much later, while sorting the keys, I noticed that it was no. 86. The address of Presidency College was 86/1. Strange, but another part of my own undergrad life seemed to have appeared in Tehatta.

These small bits and pieces received their last ovations from me as I prepared to leave. Rules demanded that I hand over everything I had taken from the college, and this included locker keys and the lockers themselves. Naturally I did so. I also returned books that I’d borrowed – books that had often helped me more in my research than the books in RKM or other noted libraries. I also began answering questions about my impending departure in a stronger affirmative.

After I had wrapped up the exam, I began wrapping up camp. And there was a lot of wrapping up to do. For someone who had lived with the express belief that this camp could not be turned into a full-fledged home away from home (see an earlier part of the series for details), I had accumulated a lot of stuff. I packed up as much as I could on the night of the 30th of May, and informed the landlady that I would be leaving the next day. The mini truck that was to carry my stuff back arrived late, and we had about an hour or so to complete all the remaining packing and loading. This was duly done, the folks sent with the truck acting with miraculous (and reckless) haste. Over that one hour, I found innumerable things that I had only known existed but never bothered to actually use, and now was carrying back in mint condition. I also realized that most of my stuff had been sourced from Kolkata, which I had been aware of but still marveled at when it was all being packed up.

Packing done, I paid the remaining money to the landlord, officially bid them well and removed my locks from the doors. The landlord informed me that he already had a person waiting to move in in early June, and so I need not be sorry about leaving. I nodded, half in relief and half disheartened to know that my camp would soon have someone else living in it. The truck revved up and set off. I checked things again, then headed out for the last time. My days of survival in Tehatta – insofar as they involved living in camp – were over.

At that time, I believed I would be going to Tehatta more than once before finally bidding goodbye. But it was not to be. Between running to the new college, heading to Bikash Bhavan and dealing with other matters, I didn’t find any time to go there beyond what was utterly necessary. And so it happened that I turned up there only after I’d obtained my release orders, and only so I could get the college release from the OIC. That done, people wished me well and I was heading back to Kolkata again, not sure when I would visit Tehatta next. The students weren’t there that day, but one of them called me as I was just getting home. Blissfully unaware that I had left, he inquired about the exams and how he should prepare. For a moment, I wondered whether I should tell him that he won’t have AM sir when classes resumed. Again, I choked and cut the call.

Thankfully, the folks there didn’t forget me, and instead planned one last hurrah. In July I was informed that a small meeting was being organized. I knew it was a farewell ceremony, a farewell ceremony for the youngest member of the staff there. The date was fixed as 4th of August, and I confirmed that I would be going.

This time, I made the journey purely for nostalgia’s sake, and clicked more photos than I had done during the entire two years. No longer was I photographing for the college website, nor for facebook. These would be memories that would be mine and mine alone, and I wished to capture everything before they slipped away.

I was greeted at the college with a lot of enthusiasm, but also some sadness. But nothing prepared me for the farewell itself. I had seen farewells before, but they had always been for people who had served long and had become pillars of the institution. I had barely served for a year and a half. Yet here I was, being spoken of in terms that made me feel warm and also somewhat embarrassed. I was being given bouquets and gifts befitting a senior teacher. I was the center of attention from teachers whose farewells I’d expected to attend. But instead, I was the one leaving.

At the end, it was my turn to speak. I’m not a great speaker, except when I’m discussing history and am in class. Or outside class. Talk history with me for hours, and I’m game. But ask me to talk about myself or some other topic, and you’d be lucky to have a dozen words from me. But on this day, words flowed. I wanted to say a lot, but held back a lot too. Even then, I spoke for a good twenty minutes, speaking of what Tehatta had given me. I spoke of how it had taught me how to handle a lot of things I would never have learned if I hadn’t joined. I talked about how it felt to be part of a budding institution instead of being bogged down by heritage. I spoke of my experiences with the staff and how I probably wouldn’t get such a staff room again.

Yet at the very end, I had to admit that the decision was mine. I had wanted to leave, and so I was leaving. It was no compulsion, but my own free choice. That said, this was the best staff room I’d probably get in a long time, probably never again. It sounded like a contradiction, but I was simply being honest. It was a contradiction, and if I were to smoothen over things, I would be lying on the very last day. That contradiction, in fact, has still not been solved and now, since I have made my decision and face its consequences, I wish to hold onto it for old times’ sake.

And so I left for the last time. We had booked a vehicle, and could all go together. This made for compelling chatter, some on the current situation, some on people’s theatre, some on Sunil Gangopadhyay and some on the meaning of academics itself. These were conversations that daily college life didn’t permit, and I was happy to be part of one, my last one in this setting perhaps. But beyond that, I watched as the fields rolled by, and wondered why I hadn’t noticed their beauty before. I had seen them enough, and had marveled at some of the jute harvesting techniques, but never at jute fields awash in the glow of the dying sun. Maybe there was a metaphor hidden in there, one that my unpoetic mind couldn’t grasp. Whatever it was, that journey back was one I would remember for a long time.

This brings me to the end of my reminiscing about Tehatta. I could talk about a lot more – I could speak about the students and their pros and cons, I could speak about how people outsmarted the Indian Railways to get seats on the 4:26, and how scandals and controversies didn’t spare Tehatta entirely. But let’s not pen every thought down. Let’s leave something for the mind to chew on, and for me to tell anyone who would be interested. Maybe my grandkids, if I do have them. But given how great a listener I am, I wouldn’t be surprised if they were more into talking with their girl/boyfriends than talking to an old man like me.

But anyway, Tehatta is over. I’m not going back, except maybe if some document is needed at some time. I’m never working there again. Maybe I’ll pass by, or even visit for a seminar. But that would be it. The Tehatta chapter in my life is over, and it brings mixed feelings with it. Diving back into the realm of feelings would make this already 3000+ essay even longer, and make for a still more intolerable read. So let’s not. But I can say this – Tehatta taught me a lot, both as a person and as a teacher. From my ability to speak Bengali, to my understanding of the needs of students from semi-urban and rural backgrounds to my surviving in a new place and becoming accustomed to the ways of the countryside, everything is due to Tehatta and Tehatta alone. I just hope I have been of some use to Tehatta too.