Remember the part where I had fantasied about living a life alone, in a city with a small apartment to call my own ? How it’d somehow seemed inspired from Camus ? Well, Camus also wrote about the protagonist, Mersault, heading off on a long bus ride to his destination. There was little description of the bus ride itself, except that perhaps it was dusty and hot, and the guy would have dozed off and woken up wondering if the ride was over yet. He would have perhaps made good use of the few stops that the bus made, refilling on water and what few snacks were available. He would have also wondered if he was getting late, and thought “fuck that” and would have dozed off again. But the dozing off would not have been comfortable because the guy next to him would have hogged the space, and the poor protagonist would have been slipping off the seat again and again. And when he reached, he would be a quarter tired, a quarter rested, and half wondering what he would have to do next.

Actually, Camus didn’t elaborate at all. Mersault got on a bus, dozed off and got down. That’s all there is to the bus ride. Given Camus’ style of writing, it is perhaps not surprising. But that doesn’t stop me from daydreaming here, sitting in front of the computer with a bottle of beer and the task of penning down all I know and felt during my days in Tehatta. But why do I bring this up ? Because before today, I had so often juxtaposed my own experiences onto Mersault’s none too memorable bus ride. But unlike Mersault, long bus rides had become a far more integral part of my life.

As I have mentioned before, the ride to Tehatta is a multi-part affair, with each part lending its own characteristic flavor to the whole affair. More importantly, there are few parts where it is mandatory to take a single mode of transport time and again, though it is very likely that you’d develop your own preferences. Also, within a single mode of transport – it is extremely likely that you’d develop a favorite bus or train, and stick with it over the jibes of your colleagues and the curses of your own body.

But where do I begin now ? Do I provide a chronological list of experiences beginning with me setting out, and ending when I reached (and the reverse during the return journey) ? Or do I take a more hazy approach to things, letting my mind wander to whatever good memories come along ? Perhaps the historian should follow the timeline strictly. In this history of my Tehatta though, I don’t want to be a professional. Let me wander, and bear with me as I do.

Early mornings have never been exactly romantic moments for me. Back when I was in school, it meant getting ready and getting through the gate before the gate closed. During my Tehatta days, it inevitably meant balancing a grumpy body with the uber-professional drivers of the Ola cab service that I used to get to the Kolkata railway station. More than once, I would take too much time doing something and end up with a cancelled trip.

But more than the incessant fear of cancellations and problems, what I would regret more is that I never got the “heading away from home” feeling. Instead, all I felt was that that day I would probably have to deal with all the problems I’d left behind in Tehatta the last time around, the classes I would take, and the journey itself.

Ola journeys occurring in the timespan of a dozen to a dozen and half minutes aren’t meant to be very memorable. Neither are the endless rushes that I forced upon myself, running across the overbridge like a madman and cursing the Maitri Express for always hogging the first platform. But there was always one pause – a pause that I took even on the last day – the one to get a newspaper. To say that I am an addict of newspapers would be wrong, since many a day passes when I’m at home with newspapers right in the next room and I couldn’t be bothered to open them up. Yet there is something about train journeys that suggest opening a newspaper (“like a Sir’) and reading on your way to work. It just seemed right. So right in fact that regardless of the newspaper concerned, my knowledge of world affairs would inevitably be updated every time I went to Tehatta.

Having verified my name from the passenger list, I would quickly board the train, take my seat and begin reading. I had a fascination for window seats, and would not part with them for my life. I still don’t, though now things are mainly limited to buses. The train would pull out, and I would be on my way.

Two hours and some change later, I would be running down the platform (or up the platform) to get through the overbridge and board a toto for the bus stand. In the final months, I’d realized that I was exiting through the wrong gate. Safety be damned, the right exit required crossing in front of the train and if it meant less wait time, I would do it.

At the end of the toto ride, I was at the bus stop. The new bus stop to be exact, since there was an old one as well. This new bus stop attracted people heading up the Karimpur, Kanainagar Ghat, Patikabari Ghat, Hridaypur, Maheshnagar and Palashipara bus routes. You’d be accosted by bus conductors looking to overstuff their buses before heading out. I’d been warned not to take these buses even though they may save some time. Instead, I would head to the right counter and get my ticket.

Though this wasn’t without its problems. As I’d mentioned, the first time I’d gone to Tehatta, I’d been accompanied by a person working at my father’s office. The second time though, I was completely on my own. In other words, I had to choose my bus on my own and do so with precision. Now I’d been told that there are two major types of buses – the Patikabari type bus and the Karimpur type bus. Further, each type was divided into the Super bus, and the slower “route” bus. The best case scenario was to get hold of a Karimpur super and head out, being sure of reaching Tehatta PWD more (or PW more as it is actually called) in a little over an hour.

But for this I had to know which bus would go to Karimpur. I learnt that the first counter was for Patikabari buses, while the second catered to Karimpur buses (and various other categories, which I learnt later). I went to the counter and asked “Karimpur ?”, the way you ask a city bus in Kolkata whether it would go to Kasba.

The guy nodded, and told another – “একটা করিমপুর কাট” Looking at me, he said – “৫০ টাকা দেন ”। I was quite unpleasantly surprised, since I knew the fare was a rather odd 28 rupees. I verified and was told that I had heard correctly. I bought the ticket, and headed up the vehicle’s stairs, preparing to take my allotted seat.

For some reason, I felt that I should have asked about Tehatta specifically. Who knows how many interweaving roads there are ? Every road that goes to Karimpur may, after all, not take me to Tehatta. The previous journey had persuaded me that getting down in the middle of the journey would be akin to getting down amidst jute fields and brick manufacturing units. Needless to say, I wanted to be absolutely sure that I was jumping onto the right bus.

So I went back and asked – “দাদা, এটা তেহট্ট যাবে তো ?”

The guy was greatly surprised – “আপনি তো বললেন করিমপুর, এখন বলছেন তেহট্ট ?”

I was getting pretty concerned by now. Had I bought the ticket to a Karimpur bound non-Tehatta bus ?

“আমি তেহট্টই যাব। পি ডাবলু ডি মোর।“

“তা বলবেন তো।“

I returned my ticket and was issued a new one, with the balance between 50 and 28 rupees. I was finally sure that I was actually headed to Tehatta.

Back in hindsight, I realise that I had fretted over nothing. The route connecting Karimpur and Krishnanagar was the state highway, with buses being unable and unwilling to navigate any deviations. Hence, the road would inevitably have led me to Tehatta. In fact, barring the Hridaypur and Mahesnagar routes, all the bus routes passed through Tehatta.

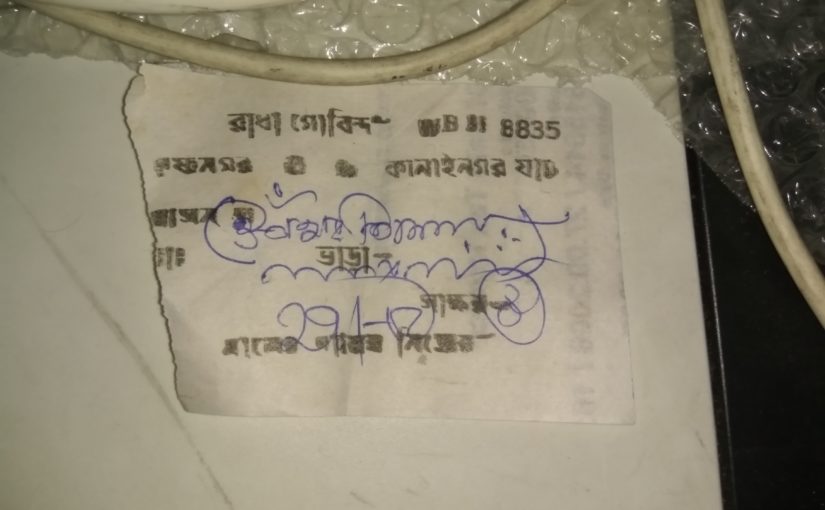

In fact, over time I decided that the Karimpur buses were probably not the best. You’d ask – what do I mean by best ? I can’t exactly say, but one criterion that came to my mind was the amount of space in the overhead bin. Now overhead bin is a term borrowed from airlines, and I should really speak of the overhead rack. This criterion persuaded me that it’d be better to take the Kanainagar Ghat bus called Radhagobindo. Or maybe it was called Chandrayan. The former was emblazoned on its side while the latter was at the front. I shall never know. Anyhow I always called it Radhagobindo because that was what the tickets said.

Now I’ve talked about the formation of preferences. Overtime, reservations in the 2S sections of the Hazarduari became a preference. As did the Radhagobindo. So much so that I would regularly inform my girlfriend (now my ex) that I’d successfully managed to board the Radhagobindo. If I did not, she was mortally worried about me, inquiring whether I had actually managed to catch a bus at all.

Interior of venerable Radhagobindo bus

Interior of venerable Radhagobindo bus

Over time the conductors and the driver of the bus came to recognize me. True to my nature, I never bothered to find out their names, or what they did apart from running the bus. This was a part of my life that was purely instrumental, and I would have little use of the information even if I obtained it. Looking back though, those faces should have had names attached to them. My memories would somehow be incomplete without that information, as I realized on the last trip. But could I, a regular for over a year and a half, ask without shame the names of those whom I’d come to form a friendly – albeit cynically pragmatic – relationship ? The names remain unknown to me, and the memories therefore incomplete.

Yet these guys – whom I knew as the short one with a balding plate, the taller one and the “others” – showed me a good deal of regard. More than once they would go out of their way to arrange a seat for me when I arrived late and the bus was already about to leave. On the days I turned up early though, I would seek out the red and gold bus and find its personnel. These personnel could be doing anything from taking a leak to having their breakfast. Yet when they turned up I would be waiting for them. After a few months, I no longer needed to tell them where I would go.

Instead, I would simply fish out my wallet while approaching the bus, locate the conductor and hand him the cash. If I was the first, he would carefully inscribe the ticket with religious symbols and text before writing the seat number and the fare amount. Then he would respectfully touch the ticket to his forehead before giving it to me. It was, for the professional of the bus, a small expression of piety and hope that the journey would go well, that perhaps enough money would be earned and the roads would treat them well. They had chosen the fast life on the high roads, and knew the risks. This was the small -and perhaps only real protection – they could muster for the journey ahead.

Even if I did not know the name of the person in front of me, I have kept some of those tickets with me. These shall form proud markers of the unique relationship that I came to had with the bus named Radhagobindo and its attendants.

One of the “first” tickets that I was lucky enough to get!

One of the “first” tickets that I was lucky enough to get!

This relationship extended to favourable seats. Indian buses are notorious for not providing every seat with equal access to window real estate. For the Radhagobindo, this discrimination ensured that the seats 1, 4, 6 and 8 had the greatest access. Indeed, these were the only ones where the seats corresponded to the entirety of a window. I would usually get 6 or 8. On the last day, I got the first ticket, and it was an 8. Again, a memory I shall cherish.

Now came the actual journey. When I’d extrapolated my own ideas onto Mersault, I had done so based on solid experience. Or to put it more aptly – bumpy, state highway grade experience. You see, Indians have a single solution to all the woes that befall riders on the highway. This solution is called the speed breaker, or as we all call it, the bumper. As the number of accidents on the highway rose, so did the number of bumpers. In fact, a single town on the route – Chapra – had at least 5-6 bumpers. One of my colleagues had calculated the bumpers as anywhere between 30-33, and this only covered the part of the road up to Tehatta.

The result of this was that I had to constantly bounce on my seat as I headed into Tehatta. But strangely, the person who could not sleep on trains and in cars learnt to sleep on that bumpy ride. Occasionally, this meant headbutting the seat or some part of the window and waking up with a painful reminder that I was in fact, on a bus.

Despite these “hazards” though, the ride soon became one of the major ways in which I could rejuvenate myself while on the road. If I got the window seat, this was not very difficult, since the person sitting next to me would inevitably act as a barrier against my falling off. But when I was the one getting the aisle seat, dreams would more often be broken by the strange feeling of being launched into mid-air. Moments later, I was scrambling to maintain my hold on the seat and not to land up in the aisle.

Yet sleep I did, on the dusty roads that led to Tehatta. When I did not, I knew exactly which stop was coming. I never got down at any of them, though eventually fear of having to disembark at one of the more nondescript stops was suppressed. Despite this pragmatic aloofness, I had memorized the people who got on, and the actual appearance of that place.

For instance, I knew that a lot of people who got on at Krishnanagar would get down at Chapra. These would include some schoolgirls and schoolboys, some professionals working in various government jobs (including teachers of the govt. college there), and students returning from tuitions with little intention of actually attending the college.

Also, I knew that at Sonpukur and Maliapota, a lot of schoolgirls would get on, getting down at Taranipur. Again, I never bothered to find out what the school was, and whether any of the girls studying there eventually came to our college. But the very look of the place told me that the bus would suddenly light up with the chatter of a number of young girls. What they talked about – I wasn’t interested in. But the fact that they came and got down ensured that I had a human GPS system working for me, without having to fish out my phone.

In fact, over time I memorized the type of people and the landmarks associated with each of the stops that I went through. While it would be of no interest to the reader, I cannot let this information be lost!

| Stop | Landmarks | People |

| Ghurni (ঘূর্ণি) | A lot of totos and a merger of two roads coming into Krishnanagar with a bust of some important person in between. | |

| Dayerbazar (দইয়েরবাজার) | A school that was quite old. The bus would stop in front of the school right on the bumper there. | Mostly students. |

| Seemanagar (সীমানগর) | A BSF camp with the 1st Battalion (and two more). This region was somewhat forested, though why only this region was forested was beyond me. That said, the presence of trees gave a temporary impression of having been taken to a hill station or being enroute to one. | Military personnel |

| Chapra Srinagar More (চাপড়া শ্রীনগর মোড় ) | The most important of the landmarks, with a huge number of people disembarking here. I had learnt that if we moved towards the border from here, we would eventually reach the Chapra Govt College | Various |

| Chapra Bazar (চাপড়া বাজার) | Literally the bazar. Also the place to meet if you’re planning on getting anything from the Chatro Sathi book house in Chapra. | Various |

| Chapra Bangalchi More (চাপড়া ব্যাঙালচী মোড় ) | The Bangalchi college was nearby. Also, the place served as a propaganda centre for shows involving Bangladeshi B-grade actors and performers | Various |

| Choto Andulia (ছোট আন্দুলীয়া) | I’m not sure this was a proper stop, but people did get down here. Also, you learned about this place from the various bank office boards. | Various |

| Hatra Bazar (হাটরা বাজার) | Smaller than either Tehatta or Chapra, this was probably the middle point of the journey (or felt like it). | Various (with preponderance of young and studious types). |

| Bada Andulia (বড় আন্দুলীয়া) | More schools, including one with what looked like a green burial epitaph that had been made part of the school wall | Students and various |

| Sonpukur (সোনপুকুর) | Another school, plus a church and a ground with a statue of Christ | Various |

| Maliapota (মালিয়াপোতা) | Nothing notable, except a single big green cross in a field. I have speculated that it is probably a grave, but have not been able to verify. | Schools and some cool dudes who hang around the girls’ schools |

| Taranipur ( তরণীপুর ) | A huge green mosque-type structure with a huge field in front of it. During winters it hosts local cricket matches and football matches, or both in tandem. Also, home to the Pathariaghata-2 Block Trinamul Office and the office of a certain Dr. A Khan. | Various, but including many schoolgirls with a blue and white uniform |

| Baliura ( বালিউরা) | A building that may have been a school, or an office, at some time. It is now no longer in use, and looms like a relic from a bygone era – perhaps an era of glory for Baliura. Also, there is a ghat where people bathe, and where I was confident the buses would end up someday given their propensity for high stakes racing. Beginning of the riverside stretch of the road. | Hardly anyone gets down here, or gets up from here for that matter. Buses often don’t bother to stop at all. I suspect this place is haunted at odd hours. |

| Tehatta PWD More (so known for the PWD offices located nearby) | My stop. Approach marked by the river on the left, a petrol pump and a small temple on the right | All people associated with Tehatta and the college. In other words, the people who matter. |

| Tehatta Howlia More ( হাউলিয়া মোড়) | My other stop. The one I took when I had to go to my camp before heading to college. | Various, including some of my students. |

The last part of my epic journey to the glorious land of Tehatta was a toto ride. Unlike the very professional, almost autorickshaw-like mentality of the Krishnanagar toto drivers, here you could have your way if you were insistent enough. As it happened, I didn’t bother being insistent and so ended up taking a Tehatta tour each day before reaching college. The tour would include trips to various schools, the occasional visit to the ghat and most often, the correctional home located on the outskirts of Tehatta.

Finally, after about five hours on the road (and rail), a turn on the Boyerbanda road would reveal the gate of my college. Depending on the month, either of the gates would be open and I would hop down, pay the amount I felt was right (which could vary between 10 and 20 rupees depending on the extra passengers picked up/dropped en route) and head in.

The journey to Tehatta Government College was complete.

Leave a Reply